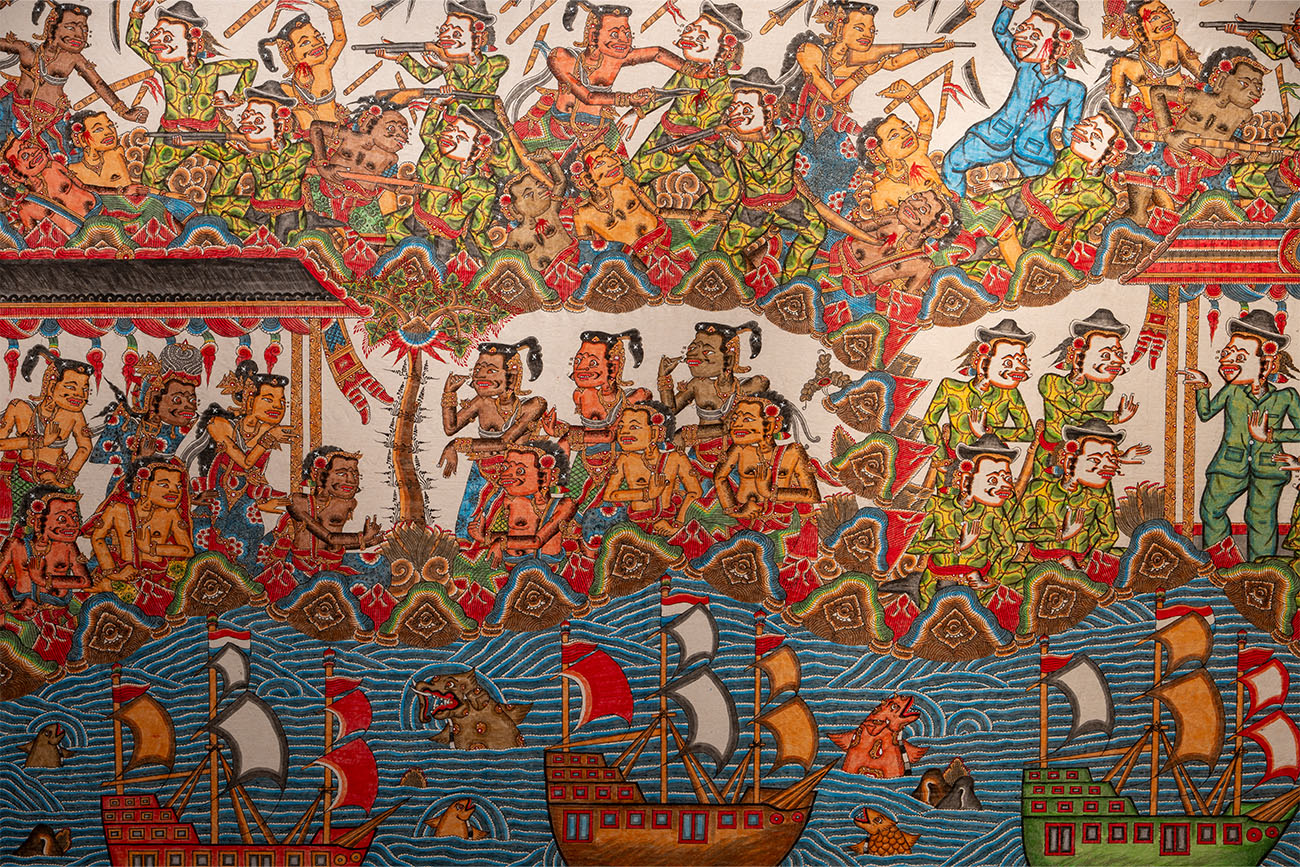

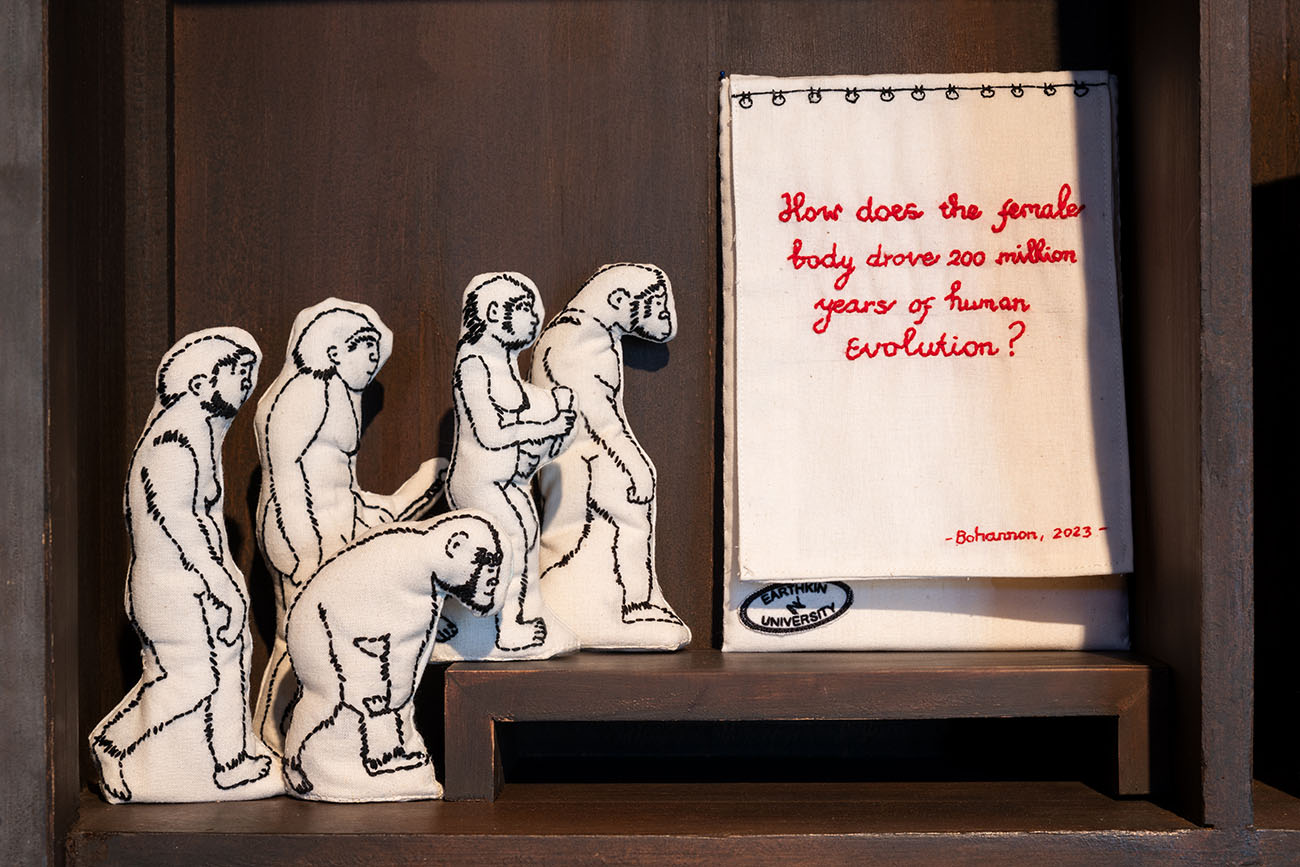

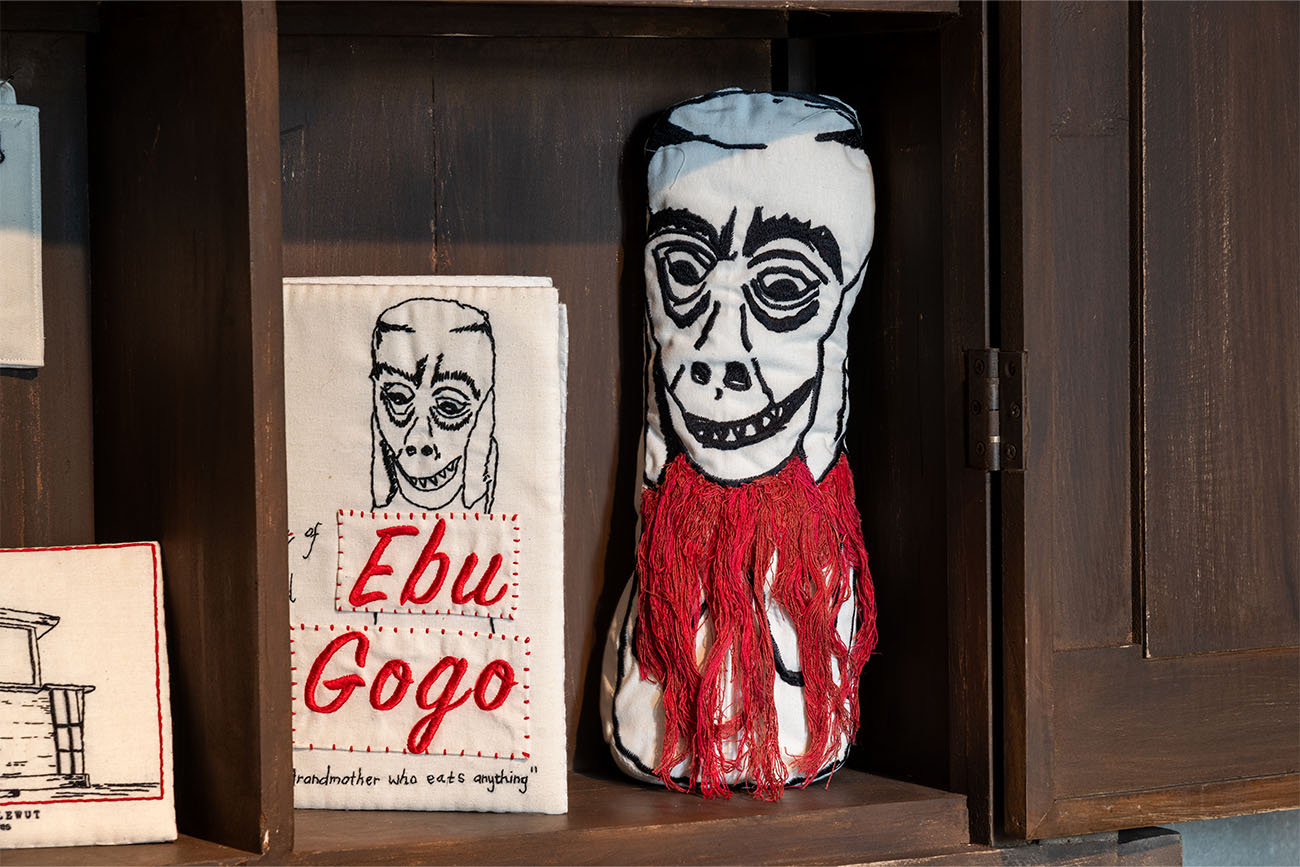

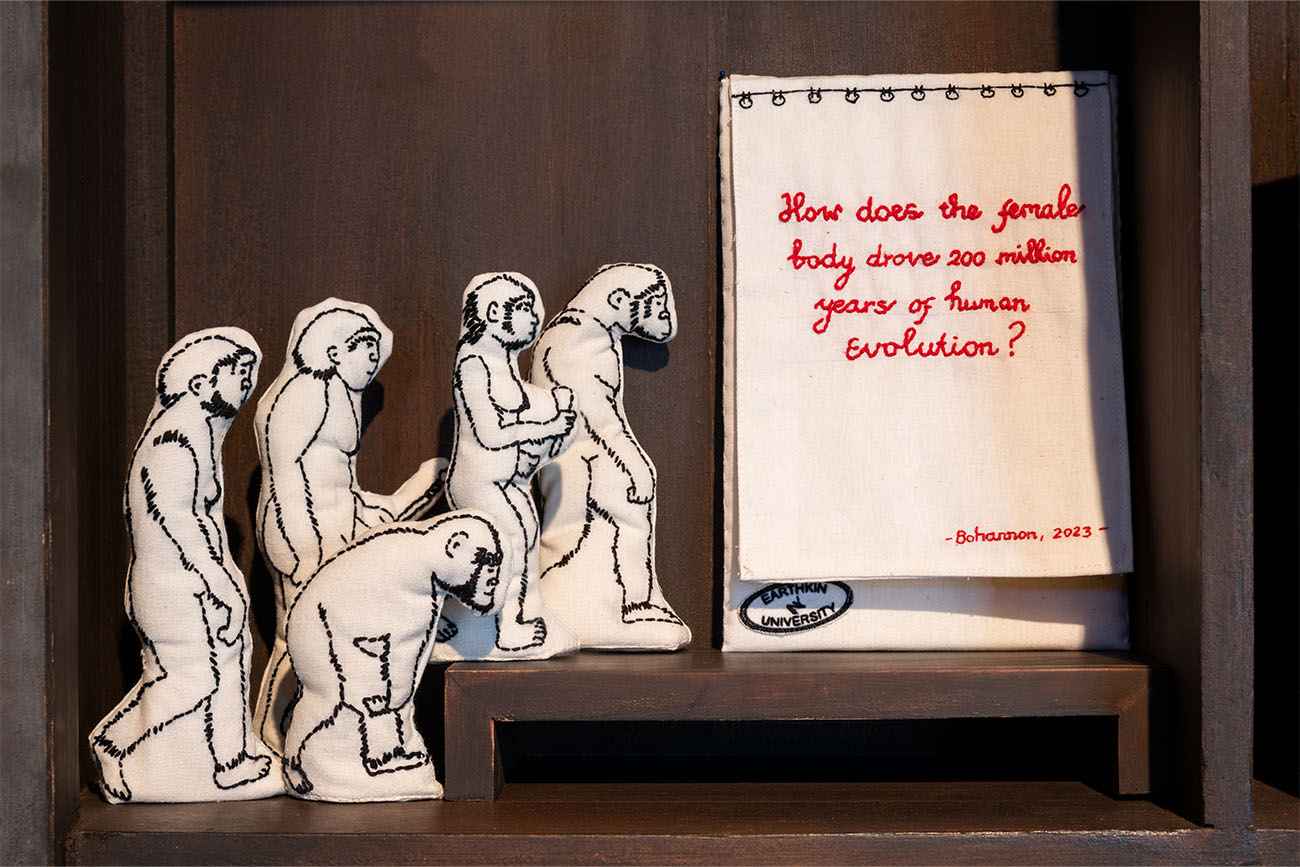

Citra Sasmita’s Timur Merah Project XV: Poetry of The Sea, Vow of The Sun (2024) is among a plethora of works across the biennial that highlight that the genealogy of ancestral knowledge can often be traced back to women. The work contemplates the life of Ida I Dewa Agung Istri Kanya, the Queen of Klungkung, Bali, who has been marginalised in Indonesia’s historical record, despite leading efforts to compile an archive of oral histories pertaining to indigenous knowledge. It consists of three cage-like tapestries embroidered with Balinese literary symbols – a winged deer, a two-headed falcon, an ouroboros – with video works ensconced inside. The Queen is also the subject of the paintings by Mangku Muriati that surround the sculpture. Exploiting the Kamasan shadow-puppet style, traditionally used to portray classical narratives in visual form, to reinterpret manuscripts with a gendered lens, the artist herself participates in the conservation of knowledge that is sidelined in the archives. Thanks to Swastika’s curatorial contribution, many of the works on display reflect on weaving and textiles as carriers of women’s knowledge, including Sasmita’s installation. Even if the medium is, at times, too heavily relied upon, some works raise critical questions about the very category of ‘women’s knowledge’. Salima Hakim’s Her Cabinet of Curiosities (2024) comprises a collection of hand-stitched replicas of archaeological artefacts and texts surrounding the 2003 excavation of a female skeleton of Homo floresiensis, an early human species, in Flores, Indonesia. By rendering the tools of scientific research in the language of a traditionally female craft, Hakim destabilises the hierarchical relationship between them.

Other works consider the forces that inhibit, rather than enable, the transfer of ancestral knowledge across time, positing or embodying strategies for its reclamation. Rully Shabara presents a museum display about the so-called Wusa people, which turns out to be entirely fictional. Yet it is utterly, unsettlingly convincing at first glance, causing us to question the trust we place in the language of museology. The Photo Kegham of Gaza: Unboxing series depicts slices of life in the city and portraits of townspeople prior to its siege in 1948, captured by the founder of its first photography studio, Kegham Djeghalian Sr. While at risk of romanticising Gaza’s past, considering Jewish settlements in the city predated the Nakba, the work makes a strong case for the importance of subjective histories: memories carried across time, in the form of photographs, make the erasure of Palestinian identity impossible.

Raven Chacon’s sound work A Wandering Breeze (2025) echoes through the abandoned sand-filled houses of Al Madam Buried Village, located in the desert between Sharjah and Oman. Built in the 1970s as a public housing project for a local Bedouin tribe, to introduce sedentism during a time of rapid modernisation, the buildings were deserted two decades later when frequent sandstorms made living conditions intractable. Developed in collaboration with Zinat Sharjah, a traditional Emirati folk band, the work is like a ghostly lament reasserting a nomadic way of life, while signaling the absurdity of the project.

Back in the city of Sharjah, Chacon’s photographs of Mariano Lake and Chilchinbeto in the Navajo Nation, the sites of similar government housing developments, draw parallels between the struggles of both communities. Further extending this call for cross-border solidarity, these works are juxtaposed with Mara TK’s From the River to the Sea (2025), in collaboration with Rana Hamida and Reem Sawan. A Māori translation of the Palestinian political slogan, the work evokes the relationship with the land, vital to both cultures: “Before the cascading here and now of these colonial projects—WE KNOW RIVERS,” the artist is quoted as saying in an accompanying text. “We are the rivers and we are the sea.”

Like Chacon’s sound work, Raafat Majzoub’s multimedia installation is site-responsive, composed of repurposed elements from 1970s buildings currently under renovation in Sharjah. Based on an earlier sculpture created with materials sourced from garbage-strewn areas of Lebanon, the work plays with perspective by bringing the crisis to a far more economically stable context. It is one of several collaborative works in the biennial, including Womanifesto’s WeMend (2023 – ongoing) project, which engages communities of women from across the world to stitch a patchwork canopy in Calligraphy Square. That many of these works respond to more than one curatorial line of inquiry is a testament to the shared knowledge, afflictions and practices of different cultures that the biennial seeks to mobilise to foster solidarity.

![Risham Syed Unn, Pami, Sut [Grain, Water, Truth]](https://legrandtour-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Biennale-de-Sharjah-Marziah-Rashid_0001_MARZIAH-RASHID_2.jpg)

![Risham Syed Unn, Pami, Sut [Grain, Water, Truth]](https://legrandtour-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/0015_4.-Risham-Syed.jpg)

![Risham Syed Unn, Pami, Sut [Grain, Water, Truth]](https://legrandtour-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/0014_5.-Risham-Syed.jpg)

![Risham Syed Unn, Pami, Sut [Grain, Water, Truth]](https://legrandtour-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/0013_6.-Risham-Syed.jpg)

![Risham Syed Unn, Pami, Sut [Grain, Water, Truth]](https://legrandtour-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/0012_7.-Risham-Syed.jpg)

![Risham Syed Unn, Pami, Sut [Grain, Water, Truth]](https://legrandtour-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/0011_8.-Risham-Syed.jpg)